The short version: Ones that don't hurt.

The long version: The reality is, for the most part, it's not WHAT exercises but HOW they exercise. People with joint hypermobility (JHM), Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS), or other connective tissue disorders struggle to find a balance between being able to exercise and not hurting. People with these conditions typically experience increased pain and joint subluxations with attempts to exercise, even when supervised by a professional. They also have high levels of muscle pain afterwards. This is especially frustrating when they are advised over and over again to be active and exercise. There are three main considerations when exercising that are overlooked with people who have hypermobility:

- Staying in joint neutral

- Proper resistance

- Using/identifying pain as a guide

1. Staying in joint neutral - that's the middle.

People with hypermobility live with their joints bouncing around in and out of the socket. They are unaware of their joint neutral position. Joint neutral is in the middle of the joint, meaning not all the way straight or all the way bent. This applies for all directions of the joint, so shoulder neutral is central in all directions. Research suggests that people with hypermobility tend to lack proprioception. Proprioception is your ability to know where your body is in space. For example, if you are walking and step on a rock, the proprioceptors will be triggered and send a signal to the brain that the foot is in a different position. The brain then responds reflexively by signaling the muscles in the side of the foot to contract, so you don't fall or twist your ankle. You can imagine what would happen if the brain didn't get the message, or got it late.

"Just because you can move to an extreme position doesn't mean you should."

Individuals with hypermobility are able to extend their joints farther than is typical without pain. Because of their low proprioception, people with JHM/EDS do not get the same feedback from their joints that a non hypermobile person would receive. So they often spend a lot of time with their joints at harmful extremes and have no idea. For joint health, they have to learn where to stop their movement in order to maintain joint stability. It is often surprising to them how small of a movement is within the safe zone. A lot of education, along with using mirrors to watch their form, is key to proper alignment and stability. In order to be successful, they need to work with a professional, whether a physical therapist, trainer, or class instructor, who can educate them and catch when they are going beyond their joint's mid range.

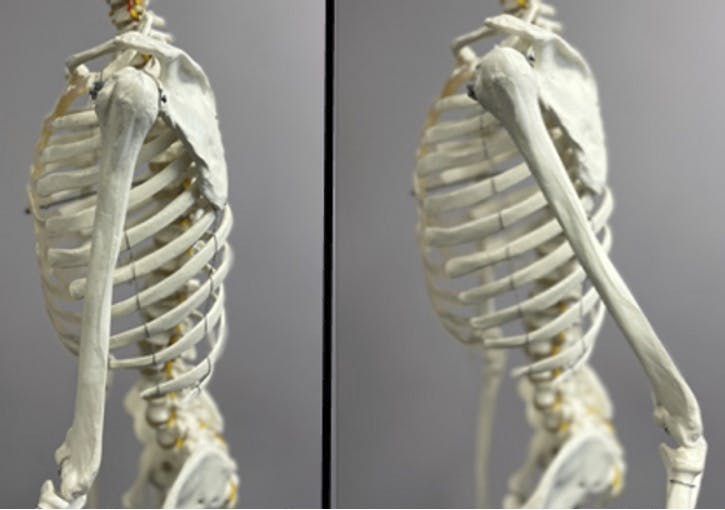

I like to explain to my patients that there is a difference between a typical workout exercise and exercising for healthy joints. Often, when working out, the aim is to use maximum resistance through the maximum range of motion, but this is not ideal for joints. Let's take a simple row for example. Typically, a rower will start with their arm all the way straight and end with their elbow bent as far as they can go behind them. This full range of motion can stress anyone's joints, because the shoulders are not designed to move behind the midline of the torso. In the shoulder, the head of the humerus (the arm bone) is the ball that composes the ball-and-socket joint. Due to the lever action of the arm, moving the elbow behind the torso will force the head of the humerus forward. If someone is hypermobile and lacking shoulder stability, they are likely subluxing the joint every time they do this, and probably also fraying their rotator cuff. So a simple exercise like a row, taken through their full mobility, can cause a lot pain, and for a person with hypermobility, they may have intense shoulder pain for days from unintentionally hyperextending or moving the joint beyond neutral.

Arm Lever Action on the Shoulder

The joints don't like to be stressed at the end of their range of motion. This is easy to visualize in the elbow. Let's examine a bicep curl for example. Typically, one starts with the elbow all the way straight, then the weight is lifted until the elbow is all the way bent, moving through the entire range of motion. Ideally, even non hypermobile people know not to lock their elbow at the end, so as not to stress the joint. A person with hypermobility has an even bigger range of motion, which gives them an even greater opportunity to damage their joint in the extreme position. Exercising with joint protection in mind means avoiding bending all the way or straightening all the way but keeping the movement within joint neutral. Depending on the severity of their condition, those with hypermobility may need to restrict their movement to only a quarter of their full range, so as to not cause any joint, tendon, or muscle damage. The common philosophy says "you'll feel better later" and "just push through the pain," but this is not a successful way to exercise. We'll get to more about that later.

The more difficult joint to control when working out is the knee. A lot of people with hypermobility lock their knees when standing, which means they're letting the knees fall back as far as they can go into hyperextension. Keeping this stance relies on the ligaments and bones instead of using the muscles, and it compresses the joints. This locking may give the feeling of strength and stability, but leads to intense knee, hip, and back pain as the joints are being stressed. It is important for those with hypermobility to learn to be able to perform exercises while keeping their knees unlocked. Standing with the knees just slightly bent and the hips sitting back, as if sitting on a high bar stool, is key for protecting the lower joints. At CGPT, we call itathletic stance. This is much harder than it seems. Many people with JHM/EDS have no idea that they are locking their joints, and consequently have incredibly weak muscles. We have had patients in the clinic who, when asked to unlock their knees, literally fell down. Starting exercises in a supported position until strength is increased may be necessary in such cases.

2. Proper Resistance - What's a light weight?

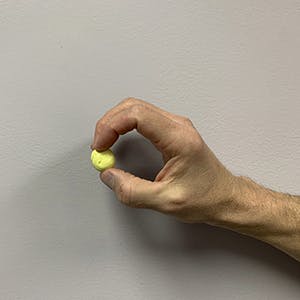

One technique that helps reduce tendon and joint pain is to build up the resistance against the tendon, so that it can tolerate a heavier load. This means starting with a load or weight that the tendon and other structures can handle (i.e., light weights). When someone is just starting to exercise, they usually know to start with lighter weights. But how light is appropriate? A "light weight" for a bicep curl is traditionally around five pounds. Since strength levels in the JHM/EDS population are often much lower than in non hypermobile patients, it is common to find that they are using weights that are too heavy for them. Many gyms don't have weights under ten pounds, so picking a light, appropriate weight is challenging. My typical weight selection for a tricep curl with a free weight for a frail, elderly woman is a one pound weight, but my last EDS patient, who was in her 20s, struggled to lift correctly with a half pound weight. She started out doing her bicep curls with a coffee mug so that she did not have any discomfort and could complete the exercise. Finding the proper starting resistance is often missed by professionals when working with hypermobile patients.

Weight selection with hypermobility is a matter of trial and error. If they are in the appropriate range of motion, the proper weight is one that allows them to maintain all joints in neutral and not have any pain or discomfort. If they can't follow those rules, they need a lighter weight. That could mean just a few ounces, like a coffee mug, or even a butter knife. There are no expectations to lift a particular weight for a particular exercise. This is where many professionals error. They, in good conscious, will give a hypermobile patient a "light weight" but it is still too much for them to handle effectively and without symptoms. Being the goodzebra who was told to exercise, the person does the exercise anyway and becomes frustrated when they hurt later. Light weight should be an appropriate weight, or more simply, a weight they can handle. That could be five pounds or three ounces. Accomplishing the exercise properly is the goal. At the end of the day, it isn't about the amount of weight one can lift, but about being capable of exercising to improve quality of life. Heavier weights will come with time.

3. Pain - pay attention to small cues.

Now we come to pain.

"No pain, No gain"

"Deal with it, you'll feel better tomorrow"

"Pain is weakness leaving the body"

Well, whoever came up with these phrases surely didn't have hypermobility. Pain is a guide that you should follow whether you are exercising or just living life. If it hurts, you need to change positions, stop, or lighten the load. But what is pain? People with hypermobility live with pain all the time. So they start ignoring low level pain at a young age. It is similar to a crying baby. If no one ever comes when the baby cries, they eventually stop crying. If the pain never stops and you don't change anything, your body eventually stops talking to you. I had one patient who ignored her pain so much that her cue that she was in pain was when she was nauseous. She had no other sense of pain or discomfort.

I have started using the phrase "Does anything feel weird or uncomfortable?" I find this phrase works well. Often patients will have a sense that something is "off," even if they are able to easily continue the exercise and wouldn't describe it as painful. So if an exercise feels off, weird, uncomfortable, or, in fact, painful, they need to check the three rules. Should they decrease the range of motion? Should they lighten the resistance? Is the pain or discomfort gone? If they are still having trouble, it's time to stop that exercise. In general it is much easier to prevent the pain by listening to the small cues, than it is to try to get rid of the large painful cues after they rear their ugly heads. The trick is knowing the small cues. Take a scan often when exercising. Pay attention to the small cues, weird feelings, aches, discomfort, feeling of going out, and popping. These are small cues that the the exercise needs to be adjusted. This will keep the strong pain levels lower and less likely later.

Exercise can be performed if a person is hypermobile. It takes a lot of mental energy for them to watch their form and pay attention to how they feel. It is imperative when exercising that they keep their joints in the neutral range and in the socket, watch their resistance levels, and pay attention to painful cues. Exercise done correctly can help with joint stability and reduce joint pain. Increased strength often increases energy levels, which helps with performing daily tasks. What person with hypermobility wouldn't like a few extra spoons in their day?

Articles

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9214343/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7021465/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7552757/

- https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/99/9/1189/5510431?login=false

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25504938/

Website